Reaganomics, a success story (2)

Time, Sep. 21, 1981

Willy De Wit: "During the Reagan Presidency (1980-1988) an economic revolution unfolded. An almost unprecedented welfare expansion took place with (a.o.) the creation of 18 million new jobs. The understanding of the mechanism behind this economic miracle is of the utmost importance. It can give us some tools for the necessary revival of the economy in Western Europe".

The third part, which will soon be published, will deal with the Laffer curve, will put Reaganomics in a historical perspective and will show how Reaganomics could be applied in Europe.

THE POOR GOT POORER AND THE RICH GOT RICHER?

“Reagan gave money away to the rich, at the expense of the poor”, many critics claim. The table below proves the contrary. At the end of the Reagan presidency, the rich paid comparatively more taxes than before. As for the poor, their share in total tax revenues decreased. There was a simple reason for this: the lower tax rates were an important incentive for the rich to expand their economic activity.The tax base had become broader, and the lower rate on the broader tax base resulted in higher tax revenues.

| Percentage of paid income tax | |||

| Income | Percentage of taxes paid | ||

| 1984 | 1986 | 1987 | |

| $0 - $15,000 | 5.8% | 4.0% | 2.8% |

| $15,000 - $30,000 | 21.1% | 16.8% | 14.7% |

| $30,000 - $50,000 | 29.0% | 25.9% | 23.0% |

| $50,000 - $100,000 | 22.0% | 24.3% | 27.7% |

| $100,000 - $200,000 | 8.6% | 10.2% | 11.9% |

| +$200,000 | 13.4% | 18.9% | 19.8% |

| 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | |

| Source: IRS | |||

In the table below we can see that the poor benefited most from the economic growth. Not only did they pay less taxes, but the 20% poorest people enjoyed an increase in income of 77 % in 9 years.

| Incomes and Social Mobility | |||

| (1991 dollars) | |||

| Average Family Income of 1977 Quintile Members in | |||

| 1977 Quintile | 1977 | 1986 | % Change |

| Bottom 20% | $15,853 | $27,998 | 77% |

| Second 20% | $31,349 | $43,041 | 37% |

| Third 20% | $43,297 | $51,796 | 20% |

| Fourth 20% | $57,486 | $63,314 | 10% |

| Top 20% | $92,531 | $97,140 | 5% |

| All | $48,101 | $56,658 | 18% |

| Source: Urban Institute | |||

HAMBURGER JOBS?

Critics claim that the growth in employment was realized mainly through the creation of crappy “hamburger jobs”. De Wit: "This is not correct. Universities could not follow to deliver enough high qualified graduates. As you can see in the following table, job growth was mainly in managerial functions. Low paid jobs in services increased very little and in farming, employment decreased".

| Job Creation in the Eighties | |||

| Jobs Created, Jan. 1982 – Dec. 1989 | |||

| Job Category | Number (Mils.) | Percentage Increase | 1989 Median Earnings |

| Managerial/Professional | 7.600 | 33.10% | $32,873 |

| Production | 2.194 | 19.00% | $25,831 |

| Technical | 6.630 | 21.80% | $20,905 |

| Operators | 1.374 | 8.20% | $19,886 |

| Services | 2.210 | 16.80% | $14,858 |

| Farming | -0.116 | -3.70% | $13,539 |

| Total | 19.892 | 20.30% | $23,333 |

| Source: Bureau of Labour Statistics (employment), Census Bureau (earnings) | |||

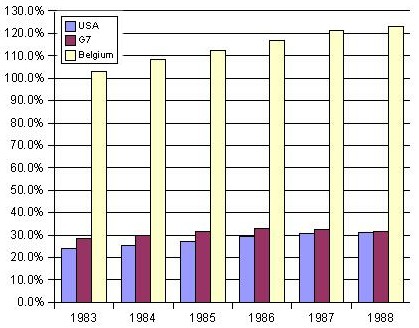

ENORMOUS PUBLIC DEBT?

It is often claimed that the budget deficit had risen to enormous proportions during the Reagan years. But between 1981 and 1989 the budget deficit increased only slightly, from 2.6% to 2.9% of GDP. The deficit peaked in 1983 to 6.1% of GDP (the Volcker recession with tight money). During the same years the Belgian budget deficit varied between 7% and 13% of GDP. The average budget deficit for the G-7 countries was only slightly lower than that of the US.

The public debt of the US as a percentage of GDP, remained below that of the G-7 countries, i.e. below 32% of GDP. But Belgian public debt, the result of years of Keynesian policy, was higher than 100% of GDP and remains around 100% at this moment.

| Net Public Debt as a percentage of GDP | ||||||

| 1983 | 1984 | 1985 | 1986 | 1987 | 1988 | |

| USA | 24.1% | 25.2% | 27.3% | 29.6% | 30.9% | 31.2% |

| G7 | 28.4% | 29.8% | 31.4% | 32.9% | 32.7% | 31.8% |

| Belgium | 103.2% | 108.2% | 112.3% | 116.7% | 121.4% | 123.1% |

WHY THE CRITICISM?

It seems strange that these figures and these facts are not better known, says Willy De Wit. But probably it is not surprising, when we consider that a right wing ("conservative") president discredited the left wing ("liberal") economic policy. Increasing social outlays doesn’t make sense when you have previously created unemployment and poverty with a wrong economic policy. Reagan has shown that the redistribution of wealth with high tax rates brings no solution. Instead of redistributing wealth, it distributes poverty. The main reason for the opposition to Reagan’s economic policy, was nevertheless that this policy was completely misunderstood at that time, mainly by the economic establishment. They did not see the fundamental difference between Keynesian thinking to stimulate demand, and the new supply-side approach by Ronald Reagan.

Keynesian thinking explained the economic achievement in terms of the level of spending. Deficit spending will keep employment high and will stimulate the economy. Cutting the deficit (for the Keynesians) would reduce spending and throw people out of work, raising the unemployment rate, reduce national income and hence produce less tax revenues. Reagan on the contrary brought a totally new perspective to economic policy. Instead of putting the emphasis on spending, supply-side economists showed that tax rates directly affect the supply of goods and services. Lowering tax rates mean better incentives to produce, to save, to invest and to take risks. In other words lower tax rates stimulate supply and not demand. The broader tax base will compensate at least partially for the lost revenue, caused by the tax cut. Higher savings will result in increased investment and unemployment will disappear. Instead of pumping up demand to stimulate the economy, reliance would be placed on improving incentives on the supply side.

The entire economic profession, along with the media could not believe that a former movie actor could come up with a revolutionary economic policy that completely contradicted the famous Keynesian theory. The reaction was fierce.

Another reason is that public opinion and most of the politicians in Europe are against the US. Roland Leuschel, a Belgian investment stategist with German roots and a good friend of Jack Kemp with whom he wrote a book in German, "Die Amerikanische Idee" (which was also published in Dutch but is out of print), dedicated a complete chapter of this book to this phenomenon: “the favorite sport of the European intelligentsia: anti-Americanism”.

REAGAN, NOT THE FIRST AND NOT THE ONLY ONE

Time, Nov. 1, 1963

Later on Erhard, as secretary for the economy, cut the high marginal tax rate in two steps: first from 95% to 63% and afterwards to 53%. The first 8000 DM earned became tax free.

The decisions taken by Ludwig Erhard allowed West-Germany to rebuild itself at a pace never seen before. No surprise that he was called the “father of the wirtschaftswunder”.

The German economic miracle cannot be explained by the Marshall Plan. Britain and France received Marshall money too, but they wasted their chances. Britain voted Labour, which brought rationing and price controls. France opted for economic protectionism, which prevented Marshal help to be used in an efficient way.

After Reagan, the theory of supply-side economics was applied in numerous countries. In Iceland, David Oddson became prime minister in 1991. He inherited a poorly performing economy burdened by heavy income taxes. He lowered the corporate tax rate from 50% to 30%. During the next five years the economy grew by 5% per year. Government income did not fall and social outlays could be maintained.

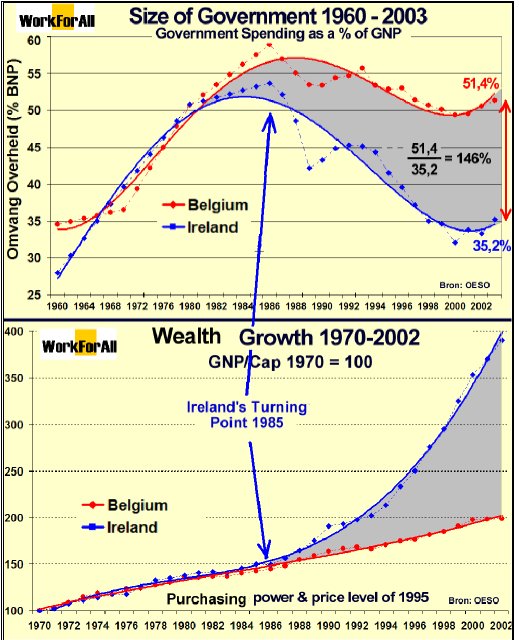

Ireland is another example. In 1987 this country was the “sick man” of Europe, with a public debt of 135 % of GDP. After the elections of 1987 a new economic policy was introduced. Corporate tax rate was reduced from 32% to 12.5% and capital gains tax was lowered from 40% to 20%. Ireland is now the fastest growing country of the EU. Japan, to the contrary, is a classic example of the failure of a Keynesian demand-side policy. The economy has been in shambles for many years and public debt has risen to a gigantic 170% of GDP.

The following graph compares government spending and GDP per capita in Ireland and Belgium between 1960 and 2003. The Irish 'turning point' came with the adoption of supply-side economics.

Reacties

Adriane

vrijdag, 22 april, 2005 - 23:28Sorry - Hat tip, Rantburg.com

Adriane

vrijdag, 22 april, 2005 - 23:27Am not good with links, but this is the scope of what we are talking about ... I think ...

http://www.dailyt...

Barbara

donderdag, 21 april, 2005 - 00:05@ de andere kijk: I missed your comment- i basically said the same thing you did. Great minds...

Barbara

donderdag, 21 april, 2005 - 00:02Wonderful post, Luc. And such high quality comments: I'm envious. My two cents: that civil procedure, "optimal state intervention" is a necessity. You see it over and over again in third world countries: productivity is greatlly reduced because capital is siphoned off by corruption and/or bureaucracy. And the same is true of over-bureaucratized developed countries- not mentioning any names.

My second point is that small amounts of venture capital are not available from private sources to third world entrepreneurs UNLESS those sources are are foundations or charities. These are very popular forms of help among church-based charities because very little money can make a huge difference in individuals' lives and the investment outlasts the presence of the donor organization (hopefully) The World Bank has touted "small capital programs" in the past, and they are effective- it's amazing what people can do if they have one more sewing machine. But private venture capital is scarce because the investment units are too small and too risky.

Adriane has a point about the ease of obtaining titles and licences, but the truth is that there are a lot of rules and no enforcement in many countries, so people ignore the law. This introduces a huge element of risk- if you get too prosperous, the powers that be need to be taken care of or you face retroactive enforcement.

By the way, Chile has proven to be an excellent example of how a free market approach works in a developing coutry. Here in the US we on the right use Chile's social security system as a model for what we would like to see here: incentives to invest for retirement but coice left entirely up to the individual, who owns the account.

Outlaw Mike

woensdag, 13 april, 2005 - 00:15Thanks Mr. Vreymans. Bookmarked those links. Very, very interesting.

Paul Vreymans-OPTIMAL STATE INTERVENTION

zondag, 10 april, 2005 - 10:18Armey studied the question of optimal state intervention and the optimal tax burden and government spending level in function of maximalizing wealth creation. In 1995 by Richard Keith "Dick" Armey (°1940), published his "Armey curve. "

Armey argues that non-existence of government causes a state of anarchy and low levels of wealth creation, because of the absence of the rule of law and protection of property rights. In such societies little incentive exists to save and invest, because of the continuous threat of expropriation. Furthermore the total lack of essential collective infrastructure leads to poor productivity and low levels of wealth creation.

Similarly, when all input and output decisions are made by government, wealth creation is also low. As Laffer argued before him, citizens then also have very little incentive to productive contribution, considering the total yield of their efforts is confiscated by the authorities.

However, if there is a mix of private and government decisions on the allocation of resources, output is larger. Initally as government builds up, the wealth creation will gradually grow larger. A state of law is being instaured, collective infrastructure such as roads, bridges and means of communication are being built, all increasing productivity. Also establishing education structures and social programs destined at perventing the exclusion of disabled for instance boost wealth creation. In the early stages of devellopement the productivity of such collective spending is far higher than the average productivity of private spending. Therefor an increase in government spending will lead to higher wealth creation.

Nevertheless additional public projects increasingly lose their productivity advantage over private investment, and heavier tax burdens for financing government spending will increasingly demotivate people to productive contribution. Social programs also loose their positive growth effect when they tend to provide incentives to leave the productive sector rather than preventing exclusion.

At some point growth-enhancing features of government spending gradually diminish and further expansion of government does no longer lead to output expansion. At that point, the marginal productivity of public spending equals the marginal productivity of private spending, and the benefits from increased government spending become zero.

Beyond this optimal point (in which situation ALL European countries have arrived ) aditional government spending lead to lower wealth creation, as ever more scarce resources are withdrawn from the private sector, where they could have been used more productively. The course of the Armey-curve therefore has a similar course as the Laffer curve; the optimum being however at substantially lower taxation level than the Laffer optimum.

Empirical optimal taxation levels were calculated in this recent paper:

PRIMO¸ PEVCIN (2004) University of Ljubljana, Does optimal size of government spending exist?

http://www.soc.ku...

MORE ABOUT THIS ON http://www.workfo...

LVB

zaterdag, 9 april, 2005 - 14:11My point is that the first requirement is a corruption-free state apparatus that protects property, enforces the rule of law, and has a judicial system that can enforce civil contracts. When all that is in place, private investment money will automatically jump on business opportunities that have a sufficient level of potential gains. If the level of potential gains is not high, or negative, then I'm calling a state-provided microcredit an allowance. Yes, they have to pay it back, but what if they can't? If the micro-entrepreneur can pay it back with interest, than it would have been (in hindsight) a good opportunity for a private investment. If not, that it was in fact a state-provided living allowance.

And don't look exclusively at banks. There is seed money in venture capital, there are angel investors etc.

In a real free-market-oriented, investment-friendly society, Barco would be more succesfull than today, and without any money that had to be taken from the taxpayer. What has happened now is that the state has forced the citizens to put part of their money (through taxes) into an investment that later proved to be succesful.

Outlaw Mike

zaterdag, 9 april, 2005 - 12:39"It depends. If you work at BARCO, sure. However, from the taxpayer's POV, for each BARCO there are several Sidmars, Cockerills, Kempense Steenkoolmijnen, etc."

Dof, with all respect, but you can't compare BARCO to Cockerill and Kempense Steenkoolmijnen. BARCO has become an international success story, producing a.o. avionics displays for the new A380 and upgrading French Rafale simulators. Well, from the late eighties the GIMV was majority shareholder of BARCO. Also, don't forget that the GIMV kick-started Plant Genetic Systems (which it sold again in 1996 for some 400 million euros) and Mietec. One must give credit where credit is due, and the GIMV is imho a (rare, admitted) example of successful government financial backing. And as De andere kijk notes, the GIMV is bound to become a private investment company itself.

"Start with microcredits, and before a single quarter has passed there will be pressure to "correct" disparaties along ethnic or racial boundaries."

Well, like I said, the formula of microcredits exists now for some 30 years (IIRC it was started by an Indian businessman, Yasul or Yameer, I forget his name) and what you state has not happened.

From what I have read, traditional private banks are less than lukewarm to start with microfinancing, and this is the ONLY reason why I suggested it would be good if governments did it in their place. And for god's sake, they are not allowances! People get a LOAN for, say, fifty US dollars, which goes a long way towards establishing a small company in, say, Sierra Leone. But ultimately they have to pay it back! What better tool is there for spoonfeeding grassroots capitalism to people in Third World countries?

de andere kijk

vrijdag, 8 april, 2005 - 09:35- I believe I read some time ago that micro-credits are being granted by the private sector, indeed not by the big banks, but by local entrepreneurs

- Innovative industries do not necessarily have to be financed by the state, there are private equity firms for example, the GIMV by the way has become a multinational private equity firm and the flemish government is considering to sell its stake in the company

- I think that we can all agree that a small, but efficient state providing the necessary insitutions is the best option, the distributive policies, they need to be criticised.

dof

vrijdag, 8 april, 2005 - 08:25"But don't you agree that it was a good thing for, say, BARCO, that there was an institution like the GIMV around to provide financial clout in the eighties?"

It depends. If you work at BARCO, sure. However, from the taxpayer's POV, for each BARCO there are several Sidmars, Cockerills, Kempense Steenkoolmijnen, etc.

Don't forget that in a normal business the board of directors controls the executive. In politics, however, there's all sorts of collusion between legislative and executive powers. Start with microcredits, and before a single quarter has passed there will be pressure to "correct" disparaties along ethnic or racial boundaries.

Outlaw Mike

vrijdag, 8 april, 2005 - 02:36Luc: "Why should governments give microcredits to starters? "

Well, DON'T think I'm a closet socialist. The ONLY reason I suggested that government should do that, is that it looks to me like "ordinary" banks don't seem to be too eager to engage completely in the world of microfinance. The reason: profits too small, the amounts in question negligible (from the P.O.V. of the bank).

After all, the formula of microfinance exists thirty years and only now it seems like we are slowly seeing a breakthough.

Now, you say: "opportunities are huge and potential profits much higher". And then I ask: why isn't microfinance a big success then in those developing countries which are relatively tranquil and stable (I am thinking of Gabon, Benin, Botswana). Caveat: I am not exactly sure about the presence of microfinancing in those countries, but if it had been a huge success, I guess i would have picked it up somewhere.

But Luc, you say: "These are the tasks of the state, and not to give financial support to entrepreneurs who are unable to attract private investments."

But don't you agree that it was a good thing for, say, BARCO, that there was an institution like the GIMV around to provide financial clout in the eighties? It is an established fact that innovative industries can't always get favourable loans (or none at all), and then the state performing the role of the banks can come in handy. I think that if the GIMV and other state-controlled risk funds had not existed, several successful high-tech industries would never have gotten beyond the spinoff state.

In the same manner, I see a similar role in developing countries for providing microcredits IF private banks are unwilling to do it. After all, it is no allowance!!! The borrowers have to pay it back!

A little bit off-topic: You know what I call an allowance? And then on a macro-scale! The silly plan to forgive the African countries' debts, as proposed by Gordon Brown. Now THAT is what I call counterproductive. Good thing Wolfowitz is World bank Director, and not Brown.

Good night, getting awfully late.

LVB

vrijdag, 8 april, 2005 - 01:42@Michael: Why should governments give microcredits to starters? Especially in poor countries where there is less competition from established players, the opportunities are huge and potential profits much higher. So, there would be sufficient interest from private investors ... if and only if there is rule of law, protection of private property (e.g. property titles) and a legal way to enforce contracts. These are the tasks of the state, and not to give financial support to entrepreneurs who are unable to attract private investments. If there is potential, private investors will come (if the state is doing its core tasks well, see above). If there is no potential, these microcredits are in fact some sort of living allowance.

Outlaw Mike

vrijdag, 8 april, 2005 - 01:31Willy, thank you.

"This can be done in numerous ways, for instance in deregulating the economy, simplifying procedures for starting a corporation, no suffocative administrative regulations for economic activities, as we have in Western Europe, encourage the private sector and not discourage it....."

Imho one VERY important action field should be added: microcredits. And although I consider myself a capitalist, I am certainly not a liberatarian because here I do see a field in which the state can and should actively play a role. I am talking about governments setting up what I should call "micro investment funds". Kind of what we have here in Belgium/Flanders with the GIMV or PMV, but on a microscale. I think governments of third world countries should much more get involved in providing bank guarantees for microcredits since the ordinary banks and private financial institutions don't seem to be too eager to really develop the concept. Good link: http://www.deverr...

Adriana: "So no, African countires like the Congo would not benefit too much from Reaganomics until the basis for a free economy, such as titles, was also or had been previously, put into place."

and De Andere Kijk: "The same thing with the absence of legal title on real estate property, resulting in the impossibility to mortgage houses as a collateral for investment... The market economy can only thrive within a framework of efficient institutions. "

This is exactly true. I know that some people on this blog tend to be libertarians and I can live with that, but personally I do not believe in a skeleton state and I am convinced that there is an important role for the government in creating the legal framework and functioning institutions. That will of course involve setting up a multitude of agencies and hiring state-paid cadres. But I think it is necessary. Think of the Somalian example: for more than ten years there has been no formal government, but curiously though it may seem at first, several businesses have thrived, a.o. Nationalink, a cell-phone provider! One of the reasons is of course that they don't pay taxes, because there is no authority to receive taxes! Well, the mere presence of some thriving business has not helped Somaia forward, that is why this year finally a new government got a chance to reassert its authority.

Of course governments should never be allowed to grow too big.

But I'd like to conclude that in the absence of at least a minimal state with sufficiently capable institutions (e.g. an authority to register land, an efficient tax system) the "Classic" Reaganomics is imho not that well suited for solving the problems of the developing world. It is however very well suited for e.g. Europe, and if US-style Reagonomics were to be applied in the EU, I guess it would result in unprecedented economic growth and massive job creation. But politics stand in the way here.

de andere kijk

donderdag, 7 april, 2005 - 22:03@Willy: great stuuf, I look forward to reading part number 3.

Just this remark: isn't it so that, because of the excessive red tape you have got to wade through to start a business, that those entrepreneurs rather prefer to go underground into the informal economy and that as a consequence, they do not have the legal certainty to get access to credit to expand and that because of it, the economy cannot develop its full potential. The same thing with the absence of legal title on real estate property, resulting in the impossibility to mortgage houses as a collateral for investment. I believe the Peruvian (?) professor Hernan De Soto wrote a lot about this subject. The market economy can only thrive within a framework of efficient institutions. You can say that such policies are part of supply-side economics, I don't mind really, but I think the term should only be used for sound macro-economic policies, otherwise it would become a catch-all phrase without specific meaning.

Willy De Wit

donderdag, 7 april, 2005 - 20:56To : The Outlaw Michael

Thanks for your reaction. Its encouraging to see that at least some people are paying some attention to the summary of my study on Reaganomics. It was indeed a lot of work to find all the figures and facts and it has involved a lot of reading on this subject. As for the translation I am glad that Luc polished a little bit my English, and put everything in a nice lay-out.

The following on your remark "....Is Reaganomics the correct tool to confront, say, Congo's economic problems..."

In my opinion it is, but not in the same way as in the US. Supply-Side economics is not limited to slashing tax rates, but more in general creating incentives to produce, to take risk, to invest etc... This can be done in numerous ways, for instance in deregulating the economy, simplifying procedures for starting a corporation, no suffocative administrative regulations for economic activities, as we have in Western Europe, encourage the private sector and not discourage it..... I do not know what the situation is in Congo, but I can give you another example for the possibility of applying Reaganomics regardless the tax burden. I think it was in 1989, when I saw a report about the dismal economic situation in PERU. The situation at that time was apparently not the consequence of the tax burden. What were the facts? The more than 250 government owned companies gobbled up half the nations' budget. Money was printed to pay the salaries of the (too many) public workers, causing an hyperinflation of 7000 %. PERU fought individual initiative with socialization and bureaucracy. In the report an example was given about an entrepreneur who wanted to legally set up a small factory in Lima. It took him 289 days of wading through red tape and $ 1.231 in bribes to corrupt government bureaucrats.

I don't know what the present situation is in PERU, but I think that many South American countries have similar diseases. In my opinion in such cases it is perfectly possible to introduce supply-side economics irrespective of the tax rates. It could be done by encourageing private initiative, slashing the role of government and simplifying considerably the suffocative administrative procedures.

Your following remark : ".....suppose that grass roots industry is able to produce new lines of fancy comsumer products (enhancing the supply), how will people without buying power procure them? "

The answer seems rather simple to me. Suppose a country is introducing supply-side economics and suppose 1 million new jobs are created. This million people will produce products (perhaps also fancy consumer products) and services. For their work they receive a salary in proportion to the value of the goods and services produced. These people are now able to buy (with their salary) the goods and services they have produced (or a similir value of products and services). There is a new balance at a higher level. (macro economy).

I don't have any more my manuals on economics. I threw them away because in my opinion they are totally useless for a macro economic policy. But I remember that the above principle has been explained by the French economist Jean Baptiste Say (1769-1832), called "the law of Say". (Apparently at that time France had some intelligent economists.)

On the economic policy of the Nazis, perhaps Martin De Vlieghere will have some comments.

In every case it was a pleasure to read you

Adriane

donderdag, 7 april, 2005 - 20:39US and most European countries have easily obtainable property titles, not so African, Asian, or even South American countries. Creation of "Government wealth" for social programs depends on the individual wealth of persons; and, individual wealth depends (among other things) on the ease with one can legaly obtain the title/licences need for ownership and business.

So no, African countires like the Congo would not benefit too much from Reaganomics until the basis for a free economy, such as titles, was also or had been previously, put into place.

However, I am not an economist, nor have I ever played on on TV.

Outlaw Mike

donderdag, 7 april, 2005 - 02:29While I agree that Reaganomics was THE means to combat the 70's economic crisis, I still think that the technique is often only applicable in those situations where the errors of the predecessor's economic policies have been so blatant that only rectifying them without implementing a wholly new economic philosophy will seem a revolution.

E.g., slashing insanely high income and corporate taxes is only possible when income and corporate taxes are, well, insanely high.

I mean, is Reaganomics the correct tool to confront, say, Congo's economic problems? The government CAN'T slash income taxes and corporate taxes for the simple reason that only very few, if any, of the Congolese are actually paying taxes. And again, suppose that grassroots industry is able to produce new lines of fancy consumer products (enhancing the supply) how will a people without buying power procure them?

Don't get me wrong: I think that Reaganomics was bound to be a major success in the States since, firstly, it was POSSIBLE in the first place to implement drastic tax breaks, and secondly, because even in our western countries with high unemployment te consumer body still has enormous amounts of money to spend.

That is why I DO think that Reaganomics would be a GIGANTIC success in Europe: there's a lot of taxes that can be reduced, and even our unemployed often have quite some money to spend. But I don't consider the implementation as realistic: the stranglehold of the left on politics, the strenght of the unions... simply exclude Reaganomics.

On the other hand, I also think that in different times Reaganomics can't always be the answer. Who will tell whether it would have produced better results than Keynesianism in the thirties?

@martin de vlieghere: I read your interesting post (the one with a.o. Goerdelers objections to Hitler). I heard of Schachts financial wizardry; the economic policy of the Nazis was the real "voodoo economics". But one cannot deny that the Keynesian elements at least INITIALLY provided millions of new jobs. In the very early years even Churchill spoke favourably of Herr Hitler. But I agree that had WWII not broken out, the system would have collapsed.